Today, universities are expected not only to teach but also to generate knowledge through research. Studies indicate that research enables universities not only to generate new knowledge but also to tackle pressing societal problems and ground their teaching in real-world situations.

Research productivity in most developing countries is still low despite institutional support. The Philippines ranked sixth out of the 10 ASEAN members in terms of journal publications. A shortage of researchers and financial resources are major factors behind low research productivity in the Global South.

While academics require funding, dedicated research time, career incentives, and supportive mentoring and training programs to be productive researchers, the problem of low research output is also aggravated by the underrepresentation of women researchers. Across the world, studies consistently show that male academics publish academic papers more than their female counterparts.

To understand these dynamics, a research team from the UP Open University and the Philippine State College of Aeronautics studied the gender difference and barriers to women’s research productivity in a teaching-focused institution. The team surveyed 104 participants from four campuses of a state college in aviation, including 65 males and 39 females.

The team is composed of Leo Mendel D. Rosario, Lloyd Lyndel P. Simporios, Finaflor F. Taylan, and Maria Lourdes T. Jarabe from UP Open University, and Sean Patrick R. Gamit and Noel R. Navigar from the Philippine State College of Aeronautics.

Women Publish Less but Collaborate More

The study found that in this educational institution, men were more likely to lead research projects, be the main authors of papers, or supervise student theses. It is important to note that when it comes to team-based research, the gap between men and women nearly disappears. In fact, women were more collaborative than men in this category, which suggests that female teachers are more involved in research as team members rather than as the lead researcher.

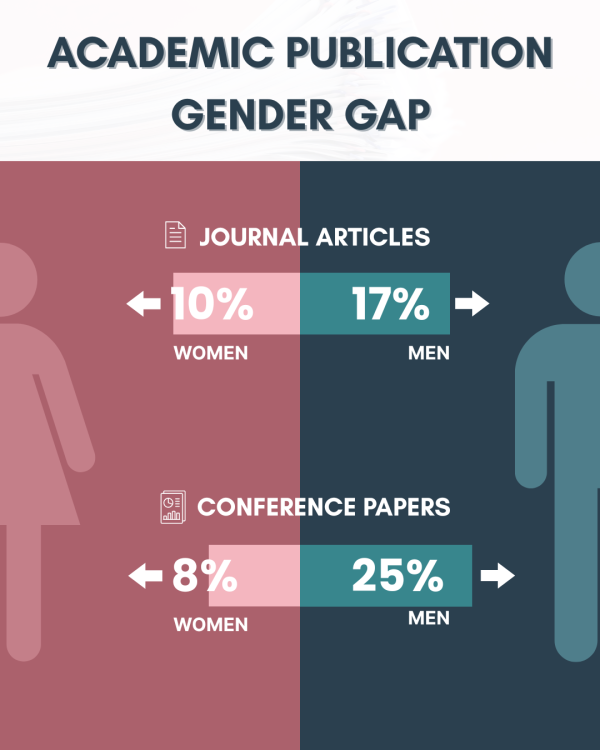

Despite this, men were still more involved in producing publications and conference papers which are highly valued in higher education. Among the participants, 17% of men had published articles compared to 10% of women, and 25% of men had presented papers at conferences versus 8% of women.

Male academics are more likely than women to publish articles and present at conferences.

The study also examined the relationship between research activities at the college and career advancement. For female teachers, promotion means getting a higher degree, like a Master’s or PhD, and accumulating years on the job. For men, promotion is more linked to seniority. This suggests that for women’s careers to advance, they need to get higher degree qualifications as well as invest more years at the institution.

Women’s workload limit research time

Although higher degrees and research experience both enable men and women to advise students theses, the study also found a significant gender gap. For men, advising students supports career advancement, but for women, the link is much weaker. Advising thesis students does not seem to help women move up in their careers nearly as much as it does for men. This suggests that women might be avoiding thesis advising due to additional but less recognized responsibilities like administrative work.

There was also a noticeable decline in the research of outputs for both married men and women. However, the number of women with children who published research was so small (only 3%), making it difficult for the authors to draw a conclusion. Overall, women produced much less research than men, even for activities that the school supported.

Talent is not the issue

So why is it hard for women teachers to be more productive in research? It is not due to a lack of talent. Women face heavier workloads and different sets of social expectations, as well as structural barriers.

Aside from their academic duties, women often handle most of the childcare, housework, and family responsibilities, leaving them little time for research. Women are also underrepresented in the aviation schools, which makes it more challenging to recruit and retain female academics.

The study provides valuable insights for teaching-focused colleges, which are common in developing countries like the Philippines. To support women in research, universities need to enhance support programs that help female professors manage their heavy workload, giving them more time for research. The authors also suggest highlighting successful female role models as sources of inspiration. Empowering women in research means valuing their work, easing their load, and breaking down barriers.

Source: Rosario LM, Gamit SP, Navigar NR, Simporios LL, Taylan FF, Jarabe ML. Intersectional Barriers to Research Productivity of Women Academics in a Philippine Teaching-Focused Institution. Asian Women. 2025 Sep;41(3):63-81. https://doi.org/10.64446/aw.2025.9.41.3.63

Written by Primo G. Garcia | Graphics from Marinela Hernandez